Community Development

Understanding the Maple Syrup Industry

We Must Cultivate Our Garden

The last ten days appear to have shaken the world in general. News junkies will have been aware of COVID-19 since the beginning of the year. I made some long flights to and from in the US in late January, and I wore a face mask, even though only a couple of cases had been diagnosed in the US and none in Latin America. I was not the only one, perhaps 1 in 20 were doing it. However, the announcement of the World Health Organization on March 11 that there was an official pandemic coincided with the beginning of the drop in the stock markets worldwide. These came only a day or two after the first two positive cases were identified here in Bolivia. Bolivia announced the grounding of flights from Europe, with the last one arriving Friday the 13th in the morning.

Vincent Omara, Uganda – Class of 2017

Future Generations University is committed to empowering local people by giving them a voice and visibility. This is exactly what alumnus Vincent Abura is doing in his job at Gulu University in Uganda.

Cape Horn and Tierra Del Fuego: The Southern tip of South America- Part III

In the eastern division, the Argentine government has promoted development by offering substantial financial inducements to people to settle and work in this region, one that diplays relatively cold weather and long, dark winter nights. A good example of the success of the plan is Ushuaia, a settlement squeezed into space bordering the Beagle Channel. Starting with a town of only around 12,000 residents the population has now increased to a city over 60,000, and as this is a port of call, or the jumping-off site, for ships heading to and from the Southern Ocean and the Antarctic Peninsula, it is bustling with visitors in the summer months. Over 200 cruise ships dock here anually.

Ushuaia City on the Beagle Channel marks the southern border of the island.

These days tourism is a major economic driving force here and records show that back in 2015 over 300,000 visitors arrived on the island, the majority (55%) from Argentina. Numerous other business activities are promoted in this eastern part of the island including extracting oil and gas, as well as peat ‘mining,’ and logging. In addition, factories that produce textiles and plastics have been constructed in economic free zones while raising beef cattle is important as this region is free of hoof-and-mouth disease.

As with most mountainous tracts, foothill areas rise up on both sides of the main spine and each altitude level comes with distinct biological constituents. In the case of Tierra del Fuego the eastern foothills of the Darwin Range lie on the dry side where the lower slopes are home to a variety of herbaceous plants including beach strawberry (Fragaria chiloensis) and calafate (Berberis buxifolia), both of which were gathered by the Yaghans for food. Stands of trees grow where conditions allow, and among these is the conifer,Pilgerodendron uviferumin the cypress family, the southernmost cone-bearing plant in the world and one often found in association with subpolar beeches, Nothofagus sp., and Winter Bark,Drimys winteri, the bark used by early travelers to prevent scurvy.

Cape Horn and Tierra Del Fuego: The Southern tip of South America- PART II

By Professor Robert Fleming

Only a few island groups on our planet have remained mostly free of human impact and with good fortune, a portion of the Tierra del Fuego Archipelago, below the Beagle Channel, is one of these. Here lies the small (244km2/94mi2) Cape Horn National Park, which encompasses both shallow marine habitats along with the island groups of Wollaston and Hermite. Cape Horn Island itself is a miniscule part of the reserve.

Some of the islands below the Beagle Channel are treeless andexhibit tundra formations as well as alpine habitats, these often intermixed with freshwater ecosystems such as peat bogs that are repleat with species of Sphagnummosses. Indeed, the whole region is a bryophyte hotspot, especially well known for its great diversity of cold-adapted liverworts and mosses.

Shaded areas on islands west of the Darwin range are conducive to fern and moss growth.

In addition, other islands in the region are partly covered with a mixture of southern evergreen forests or subpolar deciduous forests. A main component of the former is the southern beech Nothfagus betuloides, and the white-flowered Drimys winteri (in the Winteraceae family). While the deciduous forests are mostly composed of the southern beeches, Nothofagus pumilioand N. antarctica.

Cape Horn and Tierra Del Fuego: The Southern tip of South America- PART I

By Professor Robert Fleming

I am the albatross that waits for you

at the end of the world.

I am the forgotten souls of dead mariners

who passed Cape Horn

from all the oceans of the earth.

But they did not die

in the furious waves.

Today they sail on my wings

toward eternity,

in the last crack

of Antarctic winds.

– Sara Vial

A world of wind, waves, and swirling spray is home to the albatrosses of the Southern Ocean, the birds a fitting symbol for the spirits of the many mariners who have perished attempting to sail around Cape Horn (Cabo de Hornos) at the tip of South America. These roiling seas hostmany oceanic birds including petrels, skuas, and shearwaters, but the primier species are albatrosses, their seemingly effortless flight beautifully adapted to the circumpolar winds that continuously blow east between 40 degrees and 60 degrees south latitude. Beneath the ocean’s surface, the Antarctic Circumpolar Current also circles east, little impeded by any land mass except where it has to squeeze through the 800km-wide Drake Passage between the Antarctic Peninsula and South America.

Cape Horn Island as seen when approaching from the south.

Read more…

Bioacoustics in Bolivia

Shane with a local friend. Photo by Rommel

My name is Shane Palkovitz. I am a socioenvironmental specialist for the Songs of Adaptation research project at Future Generations University. The core investigations of this project focus on establishing an international baseline for biodiversity, while at the same time gathering knowledge from community members about human adaptation to climate change.

In March, I had the joy of traveling to Bolivia to work with local partners to establish a new research location. Our goal was to install four monitoring stations that will later serve as the beginning point for a larger research project.

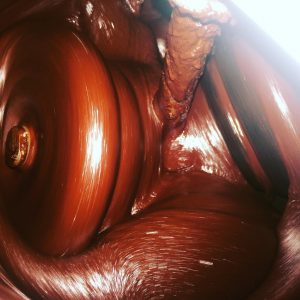

We spent the first few days trekking through the jungle, looking for sites and gathering information before installing instrumentation. Pictured below, Alejo follows as other team members venture up a stream bed on El Chocolatal, an eco-resort.

Sweet Opportunities for West Virginia

By Karen Milnes

Mike Rechlin, professor at Future Generations University, gives a tubing demonstration.

Everybody knows about Vermont maple syrup, and it’s time to put West Virginia on the map. With an estimated 0.04% (USDA—NASS) of the state’s tappable maples in production, there’s a lot of room for growth. And if this industry is doing anything, it is growing. And fast. According to a survey conducted by the Appalachian program at Future Generations, the number one component in helping our state’s maple industry expand is the need for more sap from more taps.

With ongoing innovations in the sap to syrup process, a growing number of West Virginia producers are capable of processing a lot more sap than they can obtain. Backyard syrup making is not only a mountain tradition in these parts, it’s a growing hobby as the farm and food movement sweeps across our nation. The Sweet Opportunites: Tapping West Virginia’s Maple Resource project at Future Generations University aims to start networking sap collectors and syrup producers, setting up a “hub” model, already popular in more established maple syrup producing states. What’s nice about this model is that it allows, for fairly minimal overhead, just about any landowner with maples on their property and a maple syrup producer nearby, to break into the industry with little risk. Oftentimes, sap collectors simply selling their raw sap are able to pay off the collection equipment in the first year. In a relatively short time, they can begin scaling up their operations and considering purchasing larger equipment to begin producing their own syrup.

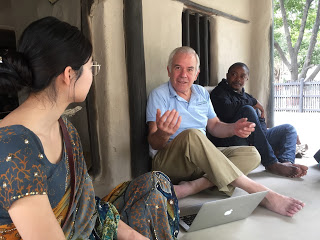

Inspiration in India

Our Learning Management Coordinator, Paula Smith, attended our field-based course in India in January. See what she has to say about the experience!

Why did you attend this field-based course on the Gandhian Method?

I was thrilled to have the opportunity to attend the Gandhi course in India. I work with the Future Generations certificate program, so I’ve helped to plan and manage this course in years past, but it was such a rewarding experience to be there in person and see all the hard work come together for a great learning experience. It helped to give me insight on how to coordinate the student experience even better going forward.

Making Maple Syrup in WV

By Mark Lambert

If you would’ve told me at this time last year that I, my wife, and our business partners would not only be producing, but delivering West Virginia Pure Maple Syrup across the state, I would’ve had to “lol.” Literally. Not just in a text or an email.

With the help of Future Generations Maple Sap Collecting and Syrup Processing certificate program, we’ve gone from wondering what our next step in the foodservice and transportation business world might be to learning how to collect sap on a commercial level. More than this, we’ve learned how to process that sap into syrup, label and bottle it for retail, and distribute not only our own finished product, but also other producers’ syrup, to retailers all over the state of West Virginia.

Alumni Feature: Melene Kabadege

Melene Kabadege is a Rwandan health professional and practitioner who attended Future Generations University as a member of the Class of 2007. A nurse with a Bachelor’s in Public Health and 16 years working for World Relief’s health and nutrition programs, Melene was seeking a way to become a true Community Health specialist.

When she met Dr. Henry Perry in 2014, a member of the Future Generations faculty at the time, and learned about the University, she realized that her dreams of bringing positive and sustainable change to her community were more achievable than she thought. She credits her education here with building her knowledge and skills in community empowerment, social change, leadership, and how to leverage and lead community successes. This empowered her to bring about lasting healthy changes in her community.

Through the Master’s program, Melene became more confident in her abilities as an agent of change and sustainable development. This inspired her to start Community Fountain Project, an NGO with the purpose of working hand-in-hand with the community to improve lives. Community Fountain Organization is currently implementing the INEZA Project, which aims to prevent under-nutrition and reduce stunting in the Kamonyi District of Rwanda.

Farmer Field and Learning School

A member of Future Generations Global Network, as are all Future Generations graduates, Melene succeeded in winning a small grant from the organization in 2017 with the purpose of implementing a Farmer Field and Learning School. Here farmers serve as teachers to their peers and join together in a farmers’ cooperative. The Project areas of intervention were: improving farming techniques, improving nutrition in the first one thousand days of a child’s life, and improving saving and learning skills. Melene’s group worked with local leaders to ensure proper project monitoring.

Hands-On Nutrition Session

After six month’s of project implantation, the team noted several behavior changes taking place in the farmers’ households. Notable outcomes include: couples participating in nutrition learning adopted better nutrition practices for pregnant women and children under age two, families have improved hygiene and feeding practices, men have taken on an increased role in child care, improved farming techniques have been taught and adopted, farmers have been mobilized towards the operation and maintenance of community works, erosion control plants have been put into place, and 25 saving and lending groups have been implemented that all remain operational.

Voluntary Savings and Loan Program

At the end of the first year, the program has been considered successful and highly appreciated by community members and leaders alike. The project was implemented in 3 out of 12 Sectors of Kamonyi District. Fundraising activities are currently ongoing with the aim to extend the INEZA Project to cover all sectors of Kamonyi District and to become a learning center for community partnership in reducing stunting and improving the life of the vulnerable people.

Congratulations to Melene on her impressive work, and our thanks for sharing her story!

Make sure to follow the blog for more stories on the inspiring work being undertaken by our incredible alumni!

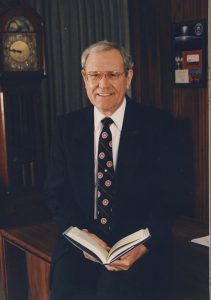

Remembering John Campbell

Future Generations lost a friend when John Campbell passed away in November of 2018. He encouraged us to take risks; specifically to push against the limits of accreditation policies to achieve the true purposes of learning. Although no longer physically here to encourage us, his message endures. “Do the right thing,” he said, “then explain you broke the rules because not doing so would have been a worse thing.”

We first became acquainted with John a decade and a half ago when he came as a member of the Higher Learning Commission accreditation team, sent here to inspect whether Future Generations was meeting the requirements of higher education and deserved accreditation. His job was to ‘check the boxes’ and make sure we were following the rules. What set John apart was that in checking the boxes, he was searching for achieving the higher purposes of the regulations.

John spoke at length with our president, Daniel C. Taylor, and the message he gave was that to achieve learning requires going forward, building on the resources present in the place. The place of Future Generations University is the world, with students from around the world who learn from the world … and most importantly shape their local worlds into better places. John recognized the potential in our idea, which was new at the time, and remained in contact with the school until his death.

Please join us in remembering John’s remarkable life with the following account, kindly provided by his family.

John Roy Campbell, PhD, DSC, DLitt

June 14, 1933-November 17, 2018

John was born near Goodman, Missouri and grew up on a small farm. He was the first of his immediate family to graduate from high school, and credited the receipt of a scholarship from the Sears Roebuck Corporation as the impetus to enroll in the University of Missouri-Columbia (MU). There he earned a B.S. with honors in Dairy Science from MU College of Agriculture in 1955, working three part-time jobs while doing so in order to fund his education.

Also during this time, a friend introduced him to Eunice Vieten, who shared his background of having grown up on a dairy farm. The two married and remained happily so until his passing, raising three children and later becoming grandparents along the way.

After receiving a fellowship to pursue Master of Science degree in Dairy Manufacturing, he served one year in the Army reserves, having been in the ROTC during college. Following that, he served two years of Active Duty in the Army’s Seventh Artillery. After discharge from the Army, he returned to Columbia to pursue his PhD in dairy cattle nutrition and physiology at MU. He continued serving as a member of the National Guard Army Reserves Field Artillery for the next 22 years, rising to the level of Lieutenant Colonel and Battery Commander of his unit. In 1983, John received The Meritorious Service Medal from the United States Army for his service.

Following completion of his PhD in 1960, John joined the MU Dairy Science faculty where he quickly rose through the ranks to become a full professor in 1968. He received nearly every award available to faculty members during his 17 years teaching there.

John taught several courses relating to dairy husbandry and animal sciences, and co-authored two textbooks. He viewed students as “our nation’s most valuable resource.” He wrote his book In Touch With Students: A Philosophy for Teachers (1972) to share his teaching philosophies with others.

In 1977, John was recruited by the University of Illinois as College of Agriculture Associate Dean and Director of Resident Instruction. In this new role, he demonstrated a zeal for the land-grant philosophy of higher education – providing educational and career opportunities for the sons and daughters of the working classes. He gained support from private individuals and corporations to establish a merit-based scholarship program to help recruit, recognize and support high-caliber students to pursue careers in agriculture, home economics and related professional fields. He selected the name Jonathan Baldwin Turner (JBT) Agricultural Merit Scholarship Program in honor of one of the initial proponents of land-grant universities. The program has been highly successful with alumni holding prominent positions in industry and at universities.

In 1983, John was named Dean of the College of Agriculture at the University of Illinois. Innovation, dedication and cooperation with people, both within and outside the College of Agriculture, were hallmarks of his deanship. His leadership was central to the College obtaining $61.2 million for construction of five new facilities. Colleagues have referred to his time at Illinois as “a golden era.”

John was appointed the fifteenth President of Oklahoma State University (OSU) on August 1, 1988 and served until 1993. At OSU he continued his student focus, championed international involvement and inter-university partnerships, and expanded distance learning. He resigned as OSU president in 1993 to teach in the OSU College of Agriculture and resume writing. In 1998, he published his fourth book Reclaiming a Lost Heritage: Land-Grant and Other Higher Education Initiatives for the Twenty-First Century, which has been used in teaching Honors Courses and educating others on the heritage of the land-grant system.

John retired from Oklahoma State University in 1999 and returned to Columbia, Missouri to take aim at new goals and opportunities. During this time, he served as a Consultant-Evaluator for the Higher Learning Commission/North Central Association and on the National University of Natural Medicine’s Board of Directors from 1998-2013. He also continued presenting lectures for numerous organizations. Having viewed the need for changes to increase societal perceptions of higher education, he wrote a novel titled Dry Rot in the Ivory Tower: A Case for Fumigation, Ventilation, and Renewal of the Academic Sanctuary, and another textbook, Companion Animals: Their Biology, Care, Health, and Management.

Throughout his professional career, John demonstrated a caring attitude toward and sincere interest in students, their careers, and personal lives. He had the privilege of teaching more than 12,000 students and published more than 100 papers. He accomplished much and left a legacy at each of the universities where he served.

He loved to tell stories and share the knowledge he had gained through his many journeys and discussions with people from “all walks of life” and was quick to extend congratulations to others on their accomplishments. At this time of loss, a smile comes to mind envisioning John sharing stories with those who preceded him in “graduating to heaven.”

U.S. Series- Part IV: Conservation that Respects People and Planet

Summary from Just and Lasting Change by Associate Professor, Noam Schimmel

An article in Britain’s Guardian newspaper recently suggested that as much as 50% of the planet needs to be set aside from human habitation to stave off mass environmental degradation and irreversible destruction of animal and plant species.

The intention behind this argument is a good one: to conserve the earth’s biodiversity and natural life forms.

These have their own intrinsic value, but also ultimately benefit people in ensuring that natural resources are protected rather than exploited to the point of unsustainability; that air, land, and water are protected in ways that promote public health, and that global warming and other forms of environmental harm are mitigated.

But there is a fallacy at the heart of the notion that the primary way to advance conservation is by removing people from nature.

People and nature are not necessarily adversaries. There are many examples, including contemporary ones, of people serving as successful guardians of nature, rather than as antagonists to the environment and its conservation.

The misguided notion that people and nature are adversaries has sullied conservation since the incarnation of the modern conservation movement. It needs to be acknowledged and addressed because it both hinders and slows environmental conservation and can contribute to denying the human rights of people who depend on nature for their livelihoods.

For many people, as individuals and as communities, their lives, values, and cultures are intimately and inextricably bound with nature.

U.S. Series- Part III: The Green Bay Packers: Community-Owned Energy

Summary from Just and Lasting Change by Associate Professor, Noam Schimmel

When you think about football, chances are you don’t think about community development, shared resources, a commitment to a non-profit ethos, and a cooperative approach to owning and managing a sports team.

But there is an open secret about one American football team that, while famous for the quality of its players and the passion of its supporters, should also be famous for its communitarian spirit, structure, and values.

As the Green Bay Packers By-Laws state, ‘The association shall be a community project intended to promote community welfare and that its purposes shall be exclusively charitable.”

This challenges the dominant paradigm of what drives sports in America and around the world: profit making. Sports are big business and they are, for the most part, run as big business.

But there are exceptions.

And it turns out that while the Green Bay Packers do make money what they do with that money and how they reinvest it in their community is what is so unique and notable, beyond their sporting excellence.

As Paz Magat, the author of this chapter in Just & Lasting Change, writes,

“The Green Bay Packers are one of the most iconic teams in American football, a team that has won thirteen championships – more than any other American professional football team – and a team that comes from the smallest city of any professional football team. So how is this team a charity? How does it promote community welfare? The answer is that instead of making money, the purpose of the team is winning for the community.”

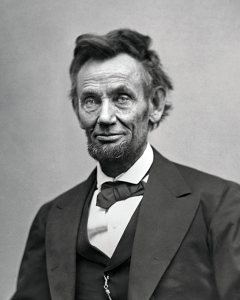

U.S. Series- Part II: The Lesser Known Lincoln

Summary from Just and Lasting Change by Associate Professor, Noam Schimmel

About Abraham Lincoln so much has been written it appears unlikely that there is more to say about him that might be new to readers. But, there is a part of Lincoln’s legacy that is genuinely underexplored and not widely known and it merits attention.

Lincoln was committed to advancing human development in a young United States in a way that was deeply democratic, progressive, and marshalled human resources in innovative ways that were ground-breaking and far-reaching for his time. The legacies of the policies and programs he advanced remain as defining features of American life today, and he had an animating vision of unity in diversity that informed those policies and programs.

We take the holiday of Thanksgiving for granted; it has become one of the defining features of American cultural life. Whatever one’s religion, ethnicity, politics, heritage – wherever one comes from – Thanksgiving is widely celebrated by a huge cross-section of Americans.

What many don’t know is that we owe Thanksgiving to Lincoln, who set it aside as a holiday of thanks that he had the foresight to recognize would unite Americans despite their many divisions. To this day, it continues to do so and to bind Americans across boundaries of difference, both real and imagined, small and profound.

U.S. Series- Part I: The White Mountain Apache: Reclaiming Self-Determination

Summary from Just and Lasting Change by Associate Professor, Noam Schimmel

An Example of SEED-SCALE in Arizona

Seed-Scale has been used by Native American communities to explore and assess their communal needs and resources and to advance development that stems from the community and reflects its needs and preferences.

The White Mountain Apache of Arizona have historically had mixed experiences of government neglect as well as government support, with government support often creating unsustainable relationships of dependency that undermined dignity and freedom.

Daniel Taylor reflects upon the history and culture of the Apache of Cibecue Valley:

“The two thousand Apache of the Cibecue Valley, in eastern Arizona, are the most isolated members of the White Mountain tribe. A high percentage of the people still speak the Apache tongue, and they try to keep the older ways alive. Older residents tell of idyllic childhoods spent in the forests with deer and other wildlife as neighbors, when Cibecue Creek still abounded with trout and beaver. They tell of times when women spent their days collecting plants for food and medicines while men and children spent their days on horses. Young people are encouraged to learn traditional stories, dances, and handicrafts and to take an active part in rituals that strengthen tribal identity and values.”

Rookie Producer’s Take on the Southern Syrup Research Symposium

How many of you know about Future Generations University’s maple syrup program?! Check out this blog by the West Virginia Maple Syrup Producer’s Association’s own Tina Barton and see what she had to say about the related symposium she attended!

Read here: https://wvmspa.org/2018/10/06/rookie-producers-take-on-the-southern-syrup-research-symposium/

Bending Bamboo

By Katie Larson

When do we learn about sustainable development?

How do we learn about sustainable development?

Who is this we that I keep mentioning?

Is sustainable development only a topic for development professionals?

Even if we learn about sustainable development as children, which children get access to the “juicy”, life-changing content, produced by the United Nations, climate scientists, and development professionals?

If you speak English, you can easily access this “juicy” content. If you are confident in English, you can go further and sift through this content. If you have cultivated your critical thinking skills, you can go even further and compare the content you are reading with the reality of sustainable development in your context.[1] Think Bloom’s Taxonomy. Then think about how English fluency fundamentally impacts who gets access to the knowledge critical for understanding and meaningfully supporting the health of our changing planet.

Now, what if you are not confident in English? Imagine that you can’t sift through the many amazing resources available on sustainable development. Maybe the only content you can access is general information. You know what I mean, the information that explains that if we drive our cars less then we can stop the polar ice caps from melting and save polar bear habitats. Two very important issues to solve, yet, superficially examined and far from many people’s day to day realities.

Those of us in the development sector know that sustainable development has many definitions and that its diverse definitions, applications, and manifestations are a result of complex contextual realities. Yes, sustainable development is certainly a concept to associate with solutions to climate change. However, sustainable development as a solution must be understood in context, in a way that values local economics, health, infrastructure, and all of the other important topics of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Here is where the study of language and the study of sustainable development are similar. According to the Communicative Approach in language learning, when learning how to communicate in another language, the learner’s context matters. Imagine you are a 10th Grade student living in rural Vietnam with a high likelihood of never traveling outside of your country. You go to English class (a required subject) and open up your textbook (published in London) and scan the lesson. The lesson asks you to imagine you are discussing your recent trip to Piccadilly Square in London. What did you see? What did you eat? How were the British people? Now ask yourself, am I going to be engaged in learning how to communicate with this kind of content? Also ask yourself, will this lesson give me skills for a future career? Students who cannot link content to context and who see no relevance in learning about things they don’t think will help them in the future, are not going to seek greater fluency in a foreign language. With content unconnected to context and irrelevant to the student’s future, English language study becomes a tool only for those few students who think they will travel and/or find employment outside of Vietnam. But the truth is, English is a global language. It can be used in rural and urban Vietnam to connect people, business opportunities, science, and funding from around the world. It can also be used to foster international collaboration on sustainable development solutions for communities.

The process is the same with sustainable development knowledge acquisition. What if the content you access is tooooo unconnected to your context? What if you don’t have the English skills to sift through the content? What if you don’t have the critical thinking skills to compare and contrast content with context? Will your sustainable development education equip you to visualize sustainable development in your context? For many, the answer is no. Arctic ice problems are important. However, if they are presented as an isolated challenge, they will seem like frivolous topics of study for someone living in a tropical river delta…say the Mekong River Delta. And those of us fluent in sustainable development know just how connected the ice caps are to our oceans and the river deltas that neighbor oceans. With superficial sustainable development education, students exit school without understanding the ways in which their actions and future careers might help or hurt Earth’s ecosystems.

Now, I have a BIG question regarding English fluency as a tool to access, sift through, and critically think about sustainable development. Can we drive English language acquisition while driving sustainable development knowledge acquisition?

This is a question that Bending Bamboo is trying to answer.

What is Bending Bamboo you might ask? Bending Bamboo is a process for acquiring intercultural, communicative, competence, confidence and collaboration (iC5) skills in English and sustainable development. Bending Bamboo does this by connecting English and sustainable development to context. It currently operates in Can Tho, Vietnam – the hub of the Mekong Delta. Over a two-year cycle of workshops and online forums, Mekong Delta teachers and professionals work together to acquire their own iC5 skills and then create a curriculum that teaches these iC5 skills to their students and employees. The first deliverable of this cycle is a teacher text. The next is a student text. Both incorporate local research on sustainable development in Vietnam and South East Asia. Both incorporate the knowledge of the teacher, farmer, tour guide, and corporate professional. They both seek to support English language and sustainable development knowledge acquisition.

In its most recent workshop in July, Bending Bamboo began to visualize a concrete answer to this BIG question.

During 60 hours of workshop learning, participants were introduced to sustainable development information and stories from local and global perspectives, in English. Local and foreign experts were brought in to share their science with the participants, in English. As proficient English speakers already, the participants could sift through the content of the workshop. Tasked with reviewing and comparing sustainable development content from here and there, teachers also cultivated their critical thinking skills. For 18 participants, this was their second Bending Bamboo workshop. For these 18 participants, post-workshop evaluations showed that both their communicative English confidence and sustainable development knowledge confidence grew!

That’s good news. Bending Bamboo participants are citizen-leaders in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam. They are knowledge bridges for their communities. These citizen-leaders are now critically interacting with local and global sustainable development discourse. Even better, these citizens are, inherently, strategically positioned to spread their knowledge. Bending Bamboo is currently leveraging this strategic positioning through the collaborative creation of the Bending Bamboo Teacher Text for grade 10-12 teachers in Vietnam. Next is the collaborative creation of a Bending Bamboo Student Text for Grades 10-12. With these two tools, participants and the Bending Bamboo team can tangibly impact a student and citizen’s ability to access and meaningfully engage with sustainable development discourse.

As Bending Bamboo continues to answer, through data, its BIG question, it also eagerly and intentionally looks forward to answering the next question. It is a BIG BIG question. Can the integrated Bending Bamboo curriculum not only drive communicative English and sustainable development knowledge acquisition, but also drive sustainable development action?

Now, just for fun, I shall end with two more questions. These are BIG BIG BIG questions to get you excited and thinking about the potential of creating and implementing, context-driven, quality education. Approximately 50% of Vietnam’s population is under age 25[2]. What happens when Vietnamese youth are confident in integrated iC5 skills for English and sustainable development? What impact will this rising generation of Vietnamese citizens have on their provincial, national, ASEAN, and global communities?

[1] Interested in this statement? Read: Powell, Mike (2006). Which Knowledge? Whose Reality? An Overview of Knowledge Used in the Development Sector. Development in Practice, 16(6), 518-532.

[2] From the General Statistics Office of Vietnam

Development Series- Part IV: Advancing Human Development in Kerala, India

Summary from Just and Lasting Change by Associate Professor, Noam Schimmel

Human development that significantly advances quality of life does not have to be expensive.

It is often assumed that to make major advances in the quality of human well-being development efforts that address healthcare, education, food security, and the well-being of women and children are necessarily extremely resource intensive and therefore dependent on massive outlays of funding to advance human security.

But this is not the case.

Successful forms of development that have been transformative in positive ways and are well documented in development literature show that human well-being can be advanced with basic resources that can be found in most communities, including in countries that lack financial resources and are classified as low income.

Put simply, financial wealth is not a prerequisite for fundamental human development.

More significantly, trust, cooperative communal efforts to pool resources and expand them, careful and equitable planning, and support of local and national government coupled with local grassroots efforts are often sufficient to advance human development.

These advances lead to tangible improvements in life expectancy, improve quality of life and enhance health outcomes, promote the realization of the human rights of children and women and human rights more broadly, expand educational opportunities, and raise incomes and improve food security.

How is this possible and where has this been done? In Kerala, India.

Kerala, a region of South India, made huge advancements in human development without being dependent on external aid for enabling this transformation.

Kerala achieved the best health and education levels of development in India already by the 1960s, and continues to sustain them, while also maintaining the highest rate of political participation in India.

But, counterintuitively, it was also the poorest state in India when it had these dramatic health and education achievements.

In this seeming contradiction we can find vitally important lessons about advancing human development which may be counterintuitive, and for that reason merit attention.

Development research attributes Kerala’s outstanding social achievements to several factors.

Daniel and Carl Taylor, pioneers of community development together with UNICEF, explain that these include political leadership that was largely genuinely interested in advancing the welfare of Kerala’s residents and was not morally corrupt, a matrilineal tradition amongst many high caste Hindus in Kerala, a church that grew in adherents and advanced greater equity amongst its values and aspirations and promoted interreligious tolerance that also received the support of Hindus, and a progressive people’s movement that advanced social reforms.

According to Taylor and Taylor, this social movement initially fought back against caste-based discrimination but continued beyond that, advancing public literacy and education, promoting land reform, and making scientific knowledge broadly available to the public which has also played a role in public advocacy for continued environmental conservation.

Momentum built on momentum in positive interlocking ways: advancing women’s rights, promoting expanded educational opportunity, and providing enhance economic opportunities for trade that were open to a broad cross-section of the population all acted synergistically to advance human development.

The high literacy rate, for example, has enabled the average Keralan to follow newspapers and hold political leadership accountable in democratic elections and in between elections.

The evidence Taylor and Taylor provide is substantive and significant: In 2001 while life expectancy was 74 years in Kerala it was 59 years in all of India. Literacy in Kerala amongst females was 87%, while it was only 39% in all of India. In 2011, Kerala was the only state in India in which there was no preference for male babies; in 1991 its gender ratio was 1,036 females to 1,000 males, compared with 927 females to 1,000 males for India as a whole.

Kerala’s successes are impressive, sustained, and genuinely life altering for individuals and for society.

Taylor and Taylor note that economic wealth did eventually result from these substantial advances in human development in Kerala.

Today Kerala enjoys both high levels of social development and economic growth and greatly increased financial resources.

It is instructive to turn to Kerala’s history to learn that opportunities abound even in places that are initially resource-poor.

Human development can be enabled and derive energy from largely indigenous sources.

To be sure, Kerala’s model is unique to Kerala and its circumstances.

But undoubtedly, it has lessons for all countries seeking to advance human development and to the United States and other countries when conceptualizing and implementing development aid.

These lessons are encouraging in their affirmation of local capacity to advance positive social change from within that draws upon domestic human resources, some – but relatively moderate support from abroad, and the values and social policies that advance equity, social justice, and human emancipation which ultimately can unleash human development and well-being.

Development Series- Part III: SEED-SCALE in Nepal

Adapted from Empowerment on an Unstable Planet: From Seeds of Human Energy to a Scale of Global Change, by Daniel Taylor, Carl E. Taylor, and Jesse O. Taylor

(All photos throughout post taken from various Future Generations activities in Nepal.)

Traditional development has not dealt kindly with Nepal and has not succeeded despite huge investments of both human and financial resources over many decades.

If the best current development practices were effective, then they should have worked in Nepal. Six decades, several billion dollars, and the careers of some of the world’s finest development professionals were invested in the kingdom to reduce poverty, illiteracy, and illness. Yet today, 30 percent of Nepal’s population remains below the poverty line, with one-fifth of the country living on less than a dollar a day; half the population is illiterate, and mortality for children under age five is sixty per thousand live births.

How is this possible and what were its causes?

There were plenty of good intentions in all the right places. Economic growth was to reduce poverty. Education and elections were to build accountable government. Health services were to double life expectancy. For each, targets were set, and programs were generously funded. But while there was progress in many measurable program indicators, in each sector dysfunction grew in terms of how system relationships were functioning. Programs that were started fell apart when funding was diverted to other programs that interested donors. Newly built school buildings and schools a few years after being built by donors looked abandoned.

This dynamic is not unique to Nepal. Indeed, it characterizes the failures of traditional development programs around the world which Nepali development projects typified.

Intentions were good, outcomes were not.

Looking at Nepal as a case study helps to understand why community-based development that is genuinely communally oriented and involves real local participation and implementation is far more likely to succeed and be sustainable than traditional development projects reflecting huge, external outlays of cash and foreign expertise, but without local participation.

Without an integrated role for the Nepali government on national and regional levels to work in a three-way partnership both with local Nepali communities and with external development and aid agencies – and the resources and expertise they bring – development in Nepal was not sustainable.

The Taylors argue that although Nepal lacked financial and human resources initially, in the 1950s, when development projects began, Nepal actually had access to extensive financial and human resources available since that time, for over sixty years. In other words, the failure of Nepal’s development trajectory is not because development was working and was simply underfunded and/or not sufficiently expanded across the country. The problem was and remains that it was not working effectively, and it was not responsive to community needs.

According to the Taylors, by 1999 the bottom fifth of Nepal’s population suffered from greater poverty, malnutrition, and lower overall human development than in 1949. Traditional development programs implemented during these fifty years did not consider how the Nepali economy in the 1950s and through the 1990s was systematically excluding a huge sector of the Nepali population.

The core reason why the quality of life had gone down for the bottom quintile was that the currency of change had shifted. In 1949, a barter economy based on human energies gave employment options to poor people; but by 1999 the monetary economy had removed labor-based options; money was now required to participate in the modern world.

Had traditional development efforts been sensitive and responsive to this reality and the challenges it created for one fifth of the population, Nepal’s development trajectory would likely have been a much different and better one.

But they were not.

Further, even the development efforts they pursued that reached some of the remaining 80% of Nepal’s population, had relatively poor results and often ended in neglect or desertion because they did not link local communities in a meaningful, participatory way with the regional and national government and with foreign aid agencies and were not communal oriented.

Pockets of development would often take place in an isolated, temporally-bound manner creating the illusion of development momentum and positive change. Once the money and human resources stopped coming in, the development projects ended, development indicators declined, and local communities had neither gained in capacities nor resources to advance their own development and sustain it.

By definition, a program of development that relies primarily on external support and that does not reflect local communal needs and participation will eventually peeter out when funding ends and when human resources experts complete whatever block of time they have committed to a particular development project and country. When they leave and when funding ends, projects decline and eventually – often – die out altogether, with no one locally available to maintain and continue them.

Thus, there were decades when it appeared that traditional development was working: roads were being built, schools constructed and staffed with teachers, the economy diversifying, and Nepalis working abroad and returning to Nepal remittances that assisted Nepalis in Nepal to raise their incomes and their human development. Hotels and restaurants opened in Katmandu raising incomes and increasing employment there.

But these economic changes and expansions were not well distributed across the country in an equitable way and many were not long lasting.

The lack of democratic accountability, a rigid and exclusionary caste system, and high levels of corruption all contributed to the failure to advance development that was genuinely and sustainably transformative.

The international community acquiesced in maintaining old-order structures. For example, during these decades not one embassy or aid agency had more than a handful of token low-caste employees in managerial positions or engaged in systematic affirmative action hiring. Development was growing into a world of appearances: outputs were measured and contracts fulfilled, but connections between programs tended to be ignored.

When the monarchy was overthrown what resulted was civil war, mass violence, and chaos. Although efforts were made to write a new constitution and find more effective forms of governance that were truly inclusive and responded to the needs of the people, corruption, dysfunction, inequality, injustice, lack of responsiveness to local and regional needs and preferences, and collapse of the rule of law characterized Nepal.

By 2010, a once-expanding infrastructure built by foreign assistance was crumbling: roads, government offices, clinics, schools, postal services, agriculture extension services, even tax collection. An increasingly corrupt government system could not maintain infrastructure that aid had built. Ancient divisions of caste and tribe persisted, crippling social advancement as half of the national population, women, still were only symbolically included in decision making.

In contrast to the failures of traditional development efforts, Nepal has had substantial success in local, community-based development efforts – though these have not been extensive enough to lift the entire country out of poverty and they have received far less support from both the Nepali government and external donors than traditional development efforts. Many of these efforts are ongoing.

Nepal is filled with such examples [of community based development]: community-based clinics and schools, forests, microcredit schemes, and water supply systems. Even more persuasive proof of people’s energies are the thousands of trails, temples, village waterspouts, and herculean terraces built without any external assistance… Another example of the diffuse, emergent manner in which the people pulled themselves forward lies in Nepal’s ecotourism industry.

But these successes, outside of several select cases such as eco-tourism, have not been able to scale-up and are limited to local, grassroots initiatives.

Nepal is perhaps unusual in that although it has a record of failed traditional development – as many countries do – it simultaneously has a record of successful community based development which many countries do not.

Nepalis knows how to lift themselves out of poverty and advance their development.

SEED-SCALE has been well demonstrated in Nepal in a variety of contexts – from community-based road and bridge building efforts that have been high quality and extremely cost effective – with lasting benefit expanding trade and enabling improved travel for access to healthcare and markets to sell goods and services and produce grown in the countryside – to a sophisticated eco-tourism enterprise and range of extensive tourism related businesses incorporating tour guides, restaurants and hotels.

Many Nepalis have adapted to the opportunities provided by tourism to increase their income and use that income to improvetheir quality of life through better healthcare, housing, and educational opportunity.

While many of these programs have not been able to expand beyond largely localized programs, if the Nepali government on the national and regional level and foreign donors and aid agencies learn from the mistakes of the past and build on the successes of SEED-SCALE, Nepal will be able to advance its own development sustainably and successfully.

Then the community development that is currently taking place on a relatively small scale could eventually characterize the country as a whole for the better of all its citizens and contribute to equitable, expansive, participatory, and sustainable human development.

Development Series- Part II: Community Development from the Grassroots

This week, we’re excited to announce that Professor Schimmel’s second post in the Development Series can be found on McGill University’s Centre for Human Rights & Legal Pluralism blog! Follow the link below to read his assessment on how the SEED-SCALE theory of social change can benefit the larger field of development.

https://www.mcgill.ca/humanrights/article/community-development-grassroots

Development Series- Part I: SEED-SCALE in Cities: Curitiba, Brazil

Summary from Just and Lasting Change by Associate Professor, Noam Schimmel

Patterns of human settlement are becoming increasingly urban and with these changes come both challenges and opportunities to advance human development.

Health Series- Part IV: Community-Based Development in Ding Xian, China

Summary from Just and Lasting Change by Associate Professor, Noam Schimmel

Go to the People.

Live with the People,

Learn from the People.

Plan with the People.

Work with the People.

Start with what they know,

Build on what they have.

Teach by showing, learn by doing.

Not a showcase, but a pattern.

Not piecemeal, but integrated.

Not odds and ends, but a system.

Not to conform, but to transform.

Not relief, but release.

-Jimmy Yen (yen Yangchu)

Health Series- Part III: Out of the Shadows: Women in Afghanistan

Summary of Just and Lasting Change- Chapter 13, by Associate Professor, Noam Schimmel

**Photos from various Future Generations activities in Afghanistan

Behavioral change to advance health is often one of the most difficult aspects of the pursuit of development.

Health Series- Part II: Transformative Low Cost Healthcare

**Photos throughout the post are from Future Generations-affiliated CHW programs around India.

It is possible to provide life saving and life sustaining healthcare at an extremely low cost using well-trained non-professional community health workers.

Health Series- Part I: Communities and Government Learning to Work Together in Peru

__________________

Over the next several months, Equity & Empowerment will be releasing entries summarizing some of our earlier work to give a glimpse of the diversity of our organization and the versatility of the SEED-SCALE method which guides us. There will be 3 themed sets (series), and each set will consist of 4 entries. We hope you enjoy the first installment in our Health Series!

__________________

Original work by Laura Altobelli, Patricia Paredes, and Carl E. Taylor

Summary by Associate Professor, Noam Schimmel

SEED-SCALE illustrates how the most significant and sustainable achievements in community development typically result from a combination of bottom-up, top-down, and outside-in interventions. When these approaches work together, synergistically, they create a powerful framework for social change.

In Peru, in 1992, when the Shining Path terrorist group was defeated, villages in the Peruvian countryside looked to create healthcare programming that had been neglected during the many years of civil war and Shining Path attacks.

The Peruvian government was initially oriented towards a traditional top-down approach of bringing skilled doctors and other medical professionals to health centers located outside the villages, with the resulting high costs this would entail.

Mt. Kinabalu: A Borneo Gem

Text & Photographs by Dr. Robert L. Fleming

“Kinabalu can be rightly considered the botanical crown jewel of Borneo, but no short paper can even superficially cover all the gems.”

Mt Kinabalu, 4095m (13,435 ft) as viewed from near the Kinabalu Park headquarters at 1524m (5000ft)

Stars dimmed as people gathered in the dark on the summit of Mt Kinabalu to quietly await the dawn. If one has climbed the last 600 meters by flashlight, ascending ladders, and guided over the granite slabs by a pale rope that doubled as a handhold, the sunrise can be quite emotional. Those of us who reached the top early could see the dots of scattered flashlights moving slowly upwards. By the time the fluffy clouds below us glowed an orange-pink, a hundred or so people had gathered on Kinabalu’s 4095m, 13,435ft summit.

Mount Kinabalu is the highest peak in Borneo at 743 km2 (287mi2). Its summit is part of a batholith– a huge granite dome that formed deep within the earth’s crust. Then, some ten million years ago, tectonic activity forced the granite up through overlying sandstone and shale. Now, thousands of years later, these sedimentary layers have eroded away to leave a stunning granitic peak, which is among the youngest stand-alone, non-volcanic mountains in the world. And one that is still rising at an average rate of about 5mm a year with growth spurts often occurring during earthquakes, such as the 6.0 magnitude quake in 2015.

How to Equip Yourself to Make the Change You Wish to See

Greetings from the Western Hemisphere Alumni!

Although the Western Hemisphere Alumni group has the smallest number of members, we have by far the largest geographical area. Just look at a map! Western Hemisphere Alumni hail from North America, the Caribbean, Central America and South America, including Canada, the U.S., Nicaragua, Haiti, Guyana, Peru, and Bolivia. We speak English, Spanish, French, and quite a few localized languages, as well. This blog introduces a few of our very dynamic female alumni. A future post will introduce some of our male alumni.

Participatory Research and Plant Breeding in Honduras: Improving Livelihoods, Transforming Gender Relations

Did you know that Future Generations University regularly hosts live research seminars with development professionals of all backgrounds from around the world?

Check out the recording of February’s seminar below on participatory research and plant breeding in Honduras, and learn how its being used to improve livelihoods while transforming gender roles!

Follow us on Facebook to keep posted on the dates of upcoming seminars and for information on how to join in!

This seminar is presented by Dr. Sally Humphries, Associate Professor, Sociology and Anthropology at the University of Guelph in Ontario.

_____________________________________

Alumni Update: Anthony Kadoma

In 2014, Anthony implemented a project on developing guidelines for disseminating practicum findings at the community level. During this project, practicum findings on the topic “Adapting Poverty Reduction Strategies at Individual, Household and Community Level: Practicum Research Conducted in Nyamanga Parish, Bufunjo Sub-county in Kyenjojo district, Western Uganda” were presented to the community members.

|

| Listening attentively to issues raised by local community members. |

Holiday Greeting from the President of Future Generations University

Meet Kelli Fleming: Future Generations University’s new Assistant Professor and Director of Learning Management!

The removal of mandatory residentials, Kelli notes, changes where the teaching energy goes. She will help maximize online activities so that they remain inviting for students. It’s important in a blended platform like ours that someone be in place to keep that energy going. Some keys to this will be in the development of new teaching artifacts, implementation of effective online simulations, and by keeping up the engagement in online forums.

The removal of mandatory residentials, Kelli notes, changes where the teaching energy goes. She will help maximize online activities so that they remain inviting for students. It’s important in a blended platform like ours that someone be in place to keep that energy going. Some keys to this will be in the development of new teaching artifacts, implementation of effective online simulations, and by keeping up the engagement in online forums. Practicing Conflict Management & More in Africa

Jonathan’s Background with Future Generations:

|

| Jonathan’s Master’s Practicum Thesis |

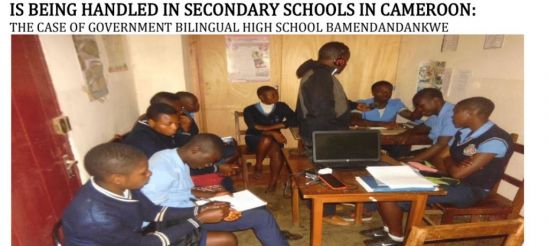

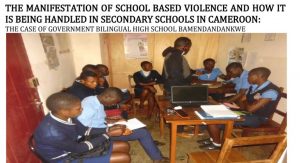

Recently, I carried out a project with the support of Future Generations University called Promotion of Peace Awareness Among Youths in Cameroon. More information on this work can be found on the Facebook page of the Cameroon Youth Partnership (www.facebook.com-cameroon-youth-partnership). This project was funded by the Davis Projects for Peace, USA and was carried out in 2015.

|

|

Nexus Fund builds & strengthens local

communities to help prevent mass attrocities

|

I completed another related project in March of 2017, entitled “Deconstructing the Terrorist Narrative among Young People in Cameroon,” funded by the Nexus Fund, USA. We came out of it with findings indicative of the process of radicalization of young people in Cameroon and produced the working document “Youth De-Radicalization Compendium.”

Liberia:

Cameroon:

This week’s blog was contributed by Jonathan Tim Nshing, a member of Future Generations University’s Class of 2015. As a school counselor by training, Jonathan has over thirteen years of service, having worked with schools, youth groups and local communities in the North West Region of Cameroon. It is also important to note that Jonathan is the founder of the Cameroon Youth Partnership. Cameroon Youth Partnership is a community-based organization aimed at the empowerment of young people through offering them information and counseling on youth related issues such as jobs, sexuality, HIV/AIDS, drug abuse, peace advocacy, and fighting violence in all its forms.

This week’s blog was contributed by Jonathan Tim Nshing, a member of Future Generations University’s Class of 2015. As a school counselor by training, Jonathan has over thirteen years of service, having worked with schools, youth groups and local communities in the North West Region of Cameroon. It is also important to note that Jonathan is the founder of the Cameroon Youth Partnership. Cameroon Youth Partnership is a community-based organization aimed at the empowerment of young people through offering them information and counseling on youth related issues such as jobs, sexuality, HIV/AIDS, drug abuse, peace advocacy, and fighting violence in all its forms. CONTACT INFORMATION

Graduation Reflections

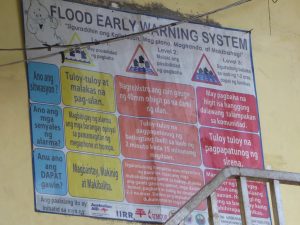

And the climax of the residential? Celebrating the graduation of students who, after 20 months of hard work, earned their MA in Applied Community Change. In a ceremony highlighting student diversity and unity, each of the regional cohorts chose a speaker and a song to share. Zerihun Damenu, Director of IIRR’s Ethiopia country program, spoke for the Africa Cohort followed by the song Africa Unity presented by all 12 students representing Ethiopia, Uganda, Sudan, Somalia, and Ghana. Mone Gurung, Program Coordinator for Future Generations Arunachal, spoke for the Himalayan Cohort, followed by the Nepali song Hami Bikaska Sahajkarta Haun (We are development facilitators) powerfully led by Bhim Nepali and accompanied by other Indian (from Arunachal Pradesh) and Nepali students. Ashley Akers of West Virginia represented the Appalachian Cohort with her speech and signing of a portion of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “moving forward” speech: “If you can’t fly then run, if you can’t run then walk, if you can’t walk then crawl, but whatever you do you have to keep moving forward.” Country Roads was appropriately chosen as the Appalachian student song but was given an international flair with students and faculty from around the globe joining in.

And the climax of the residential? Celebrating the graduation of students who, after 20 months of hard work, earned their MA in Applied Community Change. In a ceremony highlighting student diversity and unity, each of the regional cohorts chose a speaker and a song to share. Zerihun Damenu, Director of IIRR’s Ethiopia country program, spoke for the Africa Cohort followed by the song Africa Unity presented by all 12 students representing Ethiopia, Uganda, Sudan, Somalia, and Ghana. Mone Gurung, Program Coordinator for Future Generations Arunachal, spoke for the Himalayan Cohort, followed by the Nepali song Hami Bikaska Sahajkarta Haun (We are development facilitators) powerfully led by Bhim Nepali and accompanied by other Indian (from Arunachal Pradesh) and Nepali students. Ashley Akers of West Virginia represented the Appalachian Cohort with her speech and signing of a portion of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “moving forward” speech: “If you can’t fly then run, if you can’t run then walk, if you can’t walk then crawl, but whatever you do you have to keep moving forward.” Country Roads was appropriately chosen as the Appalachian student song but was given an international flair with students and faculty from around the globe joining in.

Christie is committed to ensuring that higher education is relevant and accessible to all. The benefits and opportunities available through education should not be for a select few. Towards this end, she is enthusiastic about trying new models and approaches which help to increase the reach of higher education and enable greater success. Her style is that of facilitation, empowering students to take responsibility for their own learning, and becoming life-long learners. Christie has been working at Future Generations University since 2007.

Christie is committed to ensuring that higher education is relevant and accessible to all. The benefits and opportunities available through education should not be for a select few. Towards this end, she is enthusiastic about trying new models and approaches which help to increase the reach of higher education and enable greater success. Her style is that of facilitation, empowering students to take responsibility for their own learning, and becoming life-long learners. Christie has been working at Future Generations University since 2007.

The Future and the Appalachians

|

| Class members on the first day of the Sap Collection Residential |

You can start by looking at what works, and build on that success. You can replace the energy found in coal with the human energy to innovate. You can develop partnerships between not-for-profits, government and people eager to see change. If that sounds like part of the mantra of Future Generations University; well, that’s because it is. And maybe that’s why West Virginia’s newest University just might be in the “sweet spot” when it comes to the future and the Appalachians.

|

| Participant Karen Milnes measuring trees with a diameter tape |

|

| Crew members recording plot data |

|

| Alisha and Baby Oriana making use of a Biltmore Stick |

____________________________________________________

Mike Rechlin has practiced sustainable foresty and protected areas management in the United States, Nepal, India, and Tibet for thirty years. He has extensive teaching experience and has designed educational programs for many international groups visiting the Adirondack Park of New York State. Presently retired, Mike has held academic appointments at Principia College, Paul Smith’s College, and the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. He served as the dean of Future Generations Graduate School from 2010 to 2013. He presently resides, and makes maple syrup, in Franklin, WV.

Mike Rechlin has practiced sustainable foresty and protected areas management in the United States, Nepal, India, and Tibet for thirty years. He has extensive teaching experience and has designed educational programs for many international groups visiting the Adirondack Park of New York State. Presently retired, Mike has held academic appointments at Principia College, Paul Smith’s College, and the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. He served as the dean of Future Generations Graduate School from 2010 to 2013. He presently resides, and makes maple syrup, in Franklin, WV.

Alumni Feature: Meaghan Gruber

Happy Dashain from Future Generations!

A greeting from Himalayan Regional Academic Director and Assistant Professor, Mr. Nawang Singh Gurung:

Musings of a Naturalist IV: Loango: An Elephant Eden

|

|

We rounded a bend in a small outboard to suddenly surprise a

Forest Elephant, Loxodonta cyclotis, feeding on a grassy peninsula

poking into the slow-moving Rembo Ngowe river. While this animal

did not show alarm, it did stop eating and slowly backed into the forest.

The white bar at the lower left-hand edge of this picture shows the rim

of our boat and indicates how close we were to this magnificent creature.

|

Any thought of elephants immediately brings to mind the grim straits that the Forest Elephant and all elephant species face. Elephants need space but with habitat loss and fragmentation this is a fast diminishing commodity. Besides space, rampant poaching is a dire on-going threat that will be eliminated only when human needs are adequately met and when there is no market for ivory – or bush meat. There are many on-going efforts to deal with poaching so we retain the hope that elephants will indeed survive in the wild.

Gabon had received little conservation attention and Loango was almost unknown until zoologist Michael Fey’s well-publicized on-foot transect across the Congo Basin, a journey that ended in Loango in 2000. With Longo now on the map, the forward thinking prime minister, Omar Bongo, created the National Agency for National Parks in 2002, and this body decided to protect thirteen areas of special biological interest as national parks. These now occupy ten percent of Gabon’s land area.

While elephants, as a charismatic group, attract special conservation interest, their protection and the retention of their habitat also benefits many other species which, in Gabon, includes Lowland Gorillas, Chimpanzees, Red River Hogs, African Gray Parrots, and Slender-snouted Crocodiles, all indicator species of the Congo Rainforest Biome. And also benefitting from habitat protection are Giant Kingfishers, Palm-nut Vultures, and the African Rock Python, species I had previously encountered in other areas of Africa – but never in these numbers.

|

| The Red River Hog, Potamochoerus porcus, is one of 19 species is the family Suidae. These hogs search the forest floor in tropical rainforests of West Africa and are found from the Congo Basin west to Guinea. Their preferred habitat is good forest as well as open edges of streams and marshes where they search for tubers, fruit fallen from trees, and even carrion. In addition they look for the balls of forest elephant feces which they break apart to feed on the undigested seeds of trees such as Balanites wilsoniana. While Wild Red River Hogs usually roam in small groups of up to ten animals, the large assemblages seen in Loango indicates fine habitat and good protection. |

|

| The Palm-Nut Vulture (Gypohierax angolensis), a raptor primarily of wet equatorial forests in western Africa, might best be called a vulturine eagle for its head is totally feathered, save for red facial skin, and the bird features acrobatic aerial courtship displays, rolling and diving. Besides the bird sometimes attacks living prey, occasionally picking disabled fish off the surface of the water or eyeing the occupants of a chicken coop. This vulturine eagle does feed on carrion but its primary food source is nuts of Elaeis and Raphia palms. |

|

| On occasion, most crocodiles like to haul out of the water to spend time on dry land. However, few exposed banks exist along the Mpivie or other rivers in lowland Gabon, so Slender-snouted reptiles often clamber up trunks of dead trees fallen into the river. |

|

|

The slow-moving, shaded Mpivie River is ideal habitat for Slender-snouted Crocodiles as it supports a splendid fish population and there is ample shade from the Eleias palms and other trees lining the channel. This habitat is also much favored by kingfishers as well as the African Finfoot and the large, Pell’s Owl, both rare bird species.

|

|

|

Much of the terrain inland from Gabon’s southern Atlantic coast features a mosaic of lagoons and waterways, and the people living here are masterful fishermen. Hunting in Loango National Park is not permitted but fishing for local consumption is allowed, the operations supervised by park authorities. This mid-afternoon image shows a park ranger recording the ‘take’, which includes catfish and other freshwater species while staff from the Akaka tented camp bargain for dinner.

|

|

|

Pictured is Dr. Fleming with a staff member of

Loango Lodge; the photo was taken on‘Gorilla Island’ near the

Loango National Park where there is a rehab center for rescued gorillas.

|

This week’s blog piece and photos make up the fourth installment in our Musings of a Naturalist series, courtesy of our own Dr. Robert (Bob) Fleming: Professor Equity and Empowerment/ Natural History. Having grown up in the foothills of the Himalayas in India, Bob has long been interested in the beauty of nature. This progressed into a fascination with natural history and cultural diversity, leading him to obtain his Ph.D. in zoology. He has explored many of the planet’s special biological regions, ranging from the Namib Desert in Africa to the Tropical Rainforest of the Amazon, and the Mountain Tundra biome of the Himalayas. He has worked for the Smithsonian’s Office of Ecology and the Royal Nepal Academy and, along with his father and Royal Nepal Academy Director-Lain Singh Bangdel, he wrote and illustrated “Birds of Nepal,” the first modern field guide to the birds of the region. In addition to his work with Future Generations, Bob is the director of Nature Himalayas, a sole proprietorship that he began in 1970. Through this company, Bob has led some 250 outings. He currently lives in the temperate rainforest of western Oregon in the USA’s Pacific Northwest.

Many thanks to Dr. Fleming for another great contribution!

Using the SEED-SCALE Model to Assess Access to Education in Engikaret, Tanzania

|

|

7th Year Students at ECPS.

Core Teachers: Sion and Priska.

Guest Teacher:Taylor |

Introduction

Principle One: Rising Aspirations Lead to Action

The Maasai of Engikaret live in a resource-poor and geographically isolated area, with an estimated population of 4,000. While resistant to overt cultural change, I found the Maasai of Engikaret open and willingly promote formal education as a means to generate opportunities within the community. The community’s openness to supporting formal education (such as enrollment in primary school) reflects Principal One of the SEED-SCALE model, which asserts that when promoting sustainable community programs, such as access to education, assessment leading to action should begin with evaluating the strengths of the community.

Within these strengths, I could see the hopes and dreams of parents wanting their youth to have the opportunity to attend primary school. As evidence, Engikaret has two primary schools. New Vision Primary School is a privately funded, faith-based school whereas Engikaret Community Primary School (ECPS) is a government funded, public school. While there are resource discrepancies between the two schools, the focus of my observations leads me to conclude that within the larger community context, there is a community-driven want to provide access to education for the youth of the area. Further, within the parameters of Principle One, is the need to assess how communities understand education as it relates to community health and well-being.

Officially, the community supports education, at least through the primary grades for the majority of the community’s children. I gleaned this informal information through participation in multiple Maasai community discussions. I had ample opportunities to meet with the mamas of Engikaret, who repeatedly stated that they want their children, regardless of gender, to be in school. While the position presented by the mamas highlights how the Engikaret Maasai have embraced social change through the verbal promotion of education, it is of interest that there are school-aged youth, primarily girls, who are not enrolled in either of the community’s primary schools. This observation led me to inquire about the rates of girl to boy enrollment within the public school system of Engikaret. Interviews with the public school teachers confirmed that more males are enrolled and supported in school attendance than girls. Perhaps this reflects traditions that “might create obstacles to healthy change.”

Evaluating challenges to healthy change does not mean to focus on the negative; rather Principle One acknowledges that when assessing community strengths one should not “ignore problems.” I suspect part of the reason for lower girl enrollment stems from the Maasai’s traditional gender roles. Traditional expectations of Maasai women are focused on marriage, child rearing, and home duties rather than on building gender equality through access to education. It is not to say the community does not embrace healthy change– from my observations of the Level Seven class at ECPS, I saw more female students enrolled than I had initially expected. Within the Level Seven class ,I calculated 43% of students were female, compared to 57% male. This data reflects a 23% increase in girl enrollment rates within the last generation.

|

| Mamas of Engikaret |

Principle Two: Three-way Partnerships and Malleable Leadership

|

| Maasai children herding after school and before the enrollment age of 7. NAU students: Aubrey Babcock and Taylor Lee |

Principle Three: Assessing Social Change through Community Perspectives

Conclusion

This week’s blog contributed by Taylor Lee. Taylor has a passion for promoting equitable education in underserved communities, and is currently teaching in rural Arizona with predominantly Navajo youth. While her work is focused on delivering access to high quality science education at the middle grades, embedded within her classroom work is providing youth and families with meaningful experiences that inspire students to seek post-secondary opportunities. She believes that the cycle of poverty, often associated with under-resourced communities, can be broken when youth have equitable post-secondary options readily available. She works in collaboration with community partners to provide such pathways to her students through exposure at the middle grades level.

This week’s blog contributed by Taylor Lee. Taylor has a passion for promoting equitable education in underserved communities, and is currently teaching in rural Arizona with predominantly Navajo youth. While her work is focused on delivering access to high quality science education at the middle grades, embedded within her classroom work is providing youth and families with meaningful experiences that inspire students to seek post-secondary opportunities. She believes that the cycle of poverty, often associated with under-resourced communities, can be broken when youth have equitable post-secondary options readily available. She works in collaboration with community partners to provide such pathways to her students through exposure at the middle grades level.

Equip Yourself to Make the Change You Wish to See

|

|

Gandhi’s ashram in Sevagram, India– participants in the certificate course Equip Yourself to Make the Change You Wish to See spend part of their course time here for an in-depth learning experience

|