Understanding Impacts on Life from Climate Change

This research project has launched a new website! We’ve been working to build a global team that observes and documents climate change while engaging local communities in the process. Check it out here!

This research project has launched a new website! We’ve been working to build a global team that observes and documents climate change while engaging local communities in the process. Check it out here!

Plants, Animals, Natural Systems are Adjusting—This Research is Termed Biomeridians

Earth’s climate is changing—this is known. But, below the global level, what is not known is understanding how Life locally is changing. This project outlines an approach to monitor change in the balances of plants and animals in representative habitats that encompass Life’s diversity around the world—and from this monitoring, how people, using such data, can evolve effective responses to climate change.

The university is setting up a global network of biological monitoring transects; these are called biomeridians. Biomeridians give a way to monitor change in Nature’s life balances. A biomeridian is like a ‘yardstick’ that runs from the tropics (Nature near the equator) to the arctic (Nature at the poles) but this planet-wide diversity is measured as a transect from the bottom of a mountain where the ecology is tropical up the mountain slope to where the ecology is arctic-like. One slope, then, can encapsulate the ecological diversity from the Equator to the North (or South) Pole. Future Generations University’s history in large environmental action and its history in community engagement equips the university to advance this research.

Using biomeridians on selected mountain slopes, then it is possible to measure the changes of Nature around the world. As with climate change, established relationships of plants and animals are changing around the world, then on a mountain slope their relationships will also alter: some species disappear, invasive species enter, and the balance of plants and animals will “walk uphill” with rising temperatures just as with rising Earth temperatures species are shifting upwards from the equator.

Windows on Global Climate Change

Future Generations University, through this project, is establishing biomeridians in Asia, Africa, South America, and the Pacific. The vision is ultimately to grow a framework for global tracking of climate change impacts on local life.

Future Generations University, through this project, is establishing biomeridians in Asia, Africa, South America, and the Pacific. The vision is ultimately to grow a framework for global tracking of climate change impacts on local life.

In each biomeridian, that is up one mountain slope, vegetation will be visually described. At each of these sites, then, audio monitoring will record sounds, and these will catalog bird populations, which are the most rapidly adjusting of all life forms to habitat change. The electronic sensors will run day and night, and also record temperature and humidity. This is a very sophisticated scientific study, but the personnel managing this data collection will be local communities. They will not only collect data from the monitors, they also contribute local historical knowledge to the project.

Components of climate change, of course, are already being studied: rising temperature, CO2, oceans, and the like, aggregating data from atmosphere, temperature, ocean salinity, glacial melt, species extinction, new species entering established ecologies, and the like. But with all this growing data about climate change, missing has been what the consequences will be to plants, and animals, locale-by-locale. Nature’s fundamental balances are changing in intricate ways … but how.

Phases of Our Project

First Phase—Mount Everest/ Barun Valley Biomeridian

A first biomeridian will be established off the Mt Everest massif. In Nepal’s Makalu-Barun National Park, the Barun Valley is intact from biological tropics to its arctic-like summits (Everest, but also Lhotse 4th highest and Makalu 5th highest).

Few resident life forms are above 16,000 feet, while the valley bottom contains a rich biology with tropical species such as tree ferns. There are no villages in this valley, and only three very simple trails. Insofar as any place in the Himalaya is pure wild , the Barun is that place.

Here, a partnership of local people and scientists from around the world set up the first biomeridian in the winter of 2017-2018. The methods are still being worked out, more sensors and cameras are steadily being added.

Protected as the core of Nepal’s Makalu-Barun National Park, it still holds its natural balances. At the top are no resident life forms; further down are lichens, spiders, then plants and animals. This one valley system encompasses the wild diversity of Asia; it has, for example, all three species of leopard: common spotted, the exotic snow leopard, and the rare clouded leopard.

Land quadrant monitoring stations have been designated up the valley where all species in that quadrant are visually identified. At each station, in addition to visual monitoring is also audio with recorders with enhanced microphones that monitor birds and insects not only during the day but also the night, and through the cycle of 365 days of the year.

Importantly, north of the Barun Valley and parallel to it, also falling off Everest-Lhotse-Makalu, is a valley with drier biomes. In China’s Tibet is the Gama Valley, also pristine, with its valley bottom in the warm temperate zone extending up to the arctic. The Mount Everest biomeridian project will install monitoring stations through both valleys, one in Nepal and the second in China.

For more information, visit the biomeridian project page.

Second Phase—Africa, South America, and the Pacific Biomeridians

The Mount Everest massif and Barun Valley is a first opportunity—“highest place on Earth for the highest priority.” As a monitoring method, technologies, and partnerships are perfected, other biomeridians will be added:

- A biomeridian in Africa, spanning similarly from the tropics to the arctic. Exactly which mountain slope should be chosen has not been determined. Very likely it will be in the Ruwenzori Mountains or Mount Kilimanjaro.

- The concept of biomeridian was discovered two centuries ago by Alexander von Humboldt on the Chimborazo volcano in South America. (More complete description below.) Now a permanent monitoring station will be set up on Chimborazo, and like Everest also a transect with wet/dry parallel options.

- Mauna Loa in Hawaii will be a fourth biomeridian that runs from snow-clad summits to the tropics—attractive also because this Earth’s longest monitoring of CO2 levels and because this mountain transect extends to 20,000 feet deep in the Pacific Ocean.

For more information, visit the biomeridian project page.

Third and Future Phase -- Extension to Large-scale People’s Participation

With biomeridians in place, further global monitoring becomes possible: local monitoring by people wherever they live. View the biomeridians as scientific controls, and communities around the world where people live (and in their living are changing the habitat) as experimental sites. Viewed in this manner, the world is a laboratory to monitor global climate change.

There are potentially thousands of experimental sites where human actions can be locally monitored. Impacts on life can be assessed (loss of biodiversity), and also tracking can be established for the resilience and vulnerabilities of Life (evolving bioresilience).

To set up this global tracking technology and a world-scattered workforce—a seeming massive task—actually the pieces are poised to come together. Mobile phones offer an in-place, paid-for technology.

There are several options for a workforce to systematically lead in the crowdsourcing of this global project. World Scouts offer one group of people skilled in using this technology, with discipline, able to be trained, and apolitical.

Groups other than scouts shall be encouraged to adopt this method. A world-encompassing process can start growing understanding of what is happening by the species that has come to dominate Life on Earth. What will grow is collective knowledge and across Time that tracks locale-specific impact. Evidence, as it grows, will document both impacts and solutions at local levels. Designed as it is, the costs will be manageable.

The challenge to monitor the change of Life on Earth is immense (viruses to complex organism, life In connecting people and technologies, the opportunity is to begin building understanding. The quality, diversity, and resilience of Life on Earth may be informed by what we start.

For more information, visit the biomeridian project page.

Engaging People’s Participation

Biomeridians have value beyond being transects to monitor climate change. To guide communities as they evolve their local responses, mini-biological transects (from undisturbed to highly impacted sites in their communities) will mimic the biomeridians. Paired experiments can be set up at these mini-biomeridians using the biomeridians as global standards, to inform adaptations by communities around the globe.

Biomeridians have value beyond being transects to monitor climate change. To guide communities as they evolve their local responses, mini-biological transects (from undisturbed to highly impacted sites in their communities) will mimic the biomeridians. Paired experiments can be set up at these mini-biomeridians using the biomeridians as global standards, to inform adaptations by communities around the globe.

In sharing these responses site-to-site around the world, what is also being created are experimental sites to evolve best practices in community response to climate change. Through trial and error more effective solutions can be learned. Then, if cataloged globally, what will grow will position findings of effective local action in a global forum.

In this way, communities will be literally put on the map, as data from local transects feed into global databases. Local additions will not just find climate change answers, but through their participation empower communities. Empowered action is humanity’s (and Earth’s) best hope to ultimately evolve answers in the world that comes, adapting, always fitting to changing local reality.

There is a specific role for youth in this process. They have expertise with the technologies. They are the ones who inherit today’s changing climate. Youth organizations will be key in this project (Scout troops, schools, etc.). It is likely through the leadership of youth—they already own the technologies in their mobile phones and know how to use them—that through a self-assemble of complex, multi-sensory monitoring can grow a crowd sourced solution to the global imperative

Historical Basis – Alexander von Humboldt

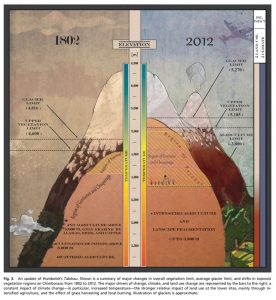

Although a project of today, two centuries ago, Alexander von Humboldt climbed the Chimborazo volcano in Ecuador. As he climbed, he painstakingly catalogued all the plants. This research two centuries ago was the bedrock for our modern concept of Nature and how Nature is distributes around the world as ecotones (tropics, subtropics, temperate, alpine, and arctic). Humboldt also showed how the Chimborazo volcano encapsulated this planetary diversity of ecology. See his graphic below.

In 2012, Humboldt’s study was repeated. Here are the findings from that 2012 comparison with his 1802 first study:

“Global climate change is driving species poleward and upward in high-latitude regions …. We revisited Chimborazo in 2012, precisely 2010 years after Humboldt’s expedition. We documented upward shifts in the distribution of vegetation zones as well as increased in maximum elevation limits of individual plant taxa of >500 meters on average. … Our findings provide evidence that global warming is strongly reshaping tropical plant distributions, consistent with Humboldt’s proposal that climate is the primary control on the altitudinal distribution of vegetation”

“Strong upslope shifts in Chimborazo’s vegetation over two centuries since Humboldt”

Naia Morueta-Holme, Dristine Engemann, Pablo Sandoval-Acuna, Jeremy D. Jonas R, Max Segnitz, and Jens-Christian Svenning. PANAS, October 13, 2015, Vol 112 no 41, pp 12741-12745

Along with Chimborazo, other historical data points also exist. When Makalu-Barun National Park was created in the 1980s, baseline botanical measurements were made. Similarly, there are baselines on the African mountains, and extensive data is available for Mauna Loa in Hawaii. In today’s era of global climate change, setting up a standardized monitoring approach in intact pristine natural transects will help grow localized understanding of the global phenomenon.

To measure life changing at planet scale, the first need is clarity on measurement method. Climate change currently is being measured by CO2, by rising temperature, aggregated species statistics, and the like. Specific dynamics are being tracked. Absent is measuring life change in its complexities. An index is needed against which the complexity of life can be measured. Or, stated another way, “pure Nature” needs to be defined—with that, a baseline will be created against which to measure change.

To measure life changing at planet scale, the first need is clarity on measurement method. Climate change currently is being measured by CO2, by rising temperature, aggregated species statistics, and the like. Specific dynamics are being tracked. Absent is measuring life change in its complexities. An index is needed against which the complexity of life can be measured. Or, stated another way, “pure Nature” needs to be defined—with that, a baseline will be created against which to measure change.

Here is a metaphor for the concept of biomeridian: Time. To make Time useful around the world, standardization was needed. First Zero Time, the point from which all time is measured. Greenwich Observatory was selected, and the instant at Greenwich when the sun crossed above, noon, became zero time. Also, standardization was required of time units: second minute, hour, year, and (moving from a lunar measure) the moment when the sun passed overhead at noon

Biological meridians are more complex; as Life is more complex than a standard march of moments. The transect is not of standardized units but change. Maximum diversity of life is where climate is most stable (the tropics), then as latitude increases toward polar regions, life diversity decreases as climate fluctuates and species become resilient to adapt to the change. Mountain transects mimic this latitudinal life zone change. Thus, one mountain slope collapses planetary latitudinal diversity and can serve as “measuring stick” that spans Earth’s biomes from the Equator to the poles.